My Trach Wake Up Call

As EMS providers, every now and then we’ll run a call that will shine a light on how little we know about some condition. This is the unfortunate fact of working in a field in which you can not know everything. I recently ran a call like that where a pediatric patient was having a trach emergency, was on a home ventilator, and had limited medical history that was available to us. While my partner and I were ultimately able to successfully manage the patient, (ABCs never fail) it still left me dissatisfied with how much I know about trachs. This post is a summary of the frantic research I did in the weeks following that call so that I would be best prepared for every possibility in trach emergencies.

Why do Tracheostomies Even Exist?

Before discussing the management of tracheostomy emergencies, it should probably be mentioned why it is even necessary for some patients to have a hole in their trachea. The two major causes of patients needing a trach are a patient needing ventilation for a long period of time or problems moving air from the mouth to the trachea.

In regards to the first reason, you may be asking why a trach would be necessary for a patient on long-term ventilation when the less invasive procedure of an endotracheal tube should work fine. After all, if endotracheal tubes are good enough for EMS to ventilate our patients shouldn’t it be good enough for long-term patients in the ICU? Unfortunately, although the ET tube is the pinnacle of prehospital airway management, they are a poor solution for long-term ventilation. Long ET tubes do not allow easy suctioning of secretions as compared to the short dual-lumen trach. With ventilated patients being unable to cough up mucus, they are entirely dependent on external suctioning. If the mucus is unable to be properly cleared, these patients are at risk of contracting pneumonia. Another risk of keeping an ET tube in a patient for too long is a nasty condition called subglottic stenosis, where the constant pressure of the ET tube cuff causes the area below the vocal cords to scar. As the above reasons illustrate, human bodies are not designed to have a tube down their throat for too long, which is why you will see long-term vent patients having trachs. (Lin 2015)

The other reason why a trach may be necessary is that there is a mass / obstruction in the upper airway preventing air movement. All the firefighters reading this likely are all too familiar with obstructive sleep apnea in one of their coworkers. In obstructive sleep apnea, the muscles of the upper airway relax too much and end up blocking airflow. A tracheostomy is used in severe cases of obstructive sleep apnea, since a trach bypasses the occasionally-blocked upper airway. Other upper airway obstructions can include a cancerous mass or trauma that makes part of the upper airway nonfunctional. In addition, the potential for an airway obstruction can be considered an indication for a trach, like in a TBI patient who is no longer able to protect their own airway. (Cheung 2014)

Tracheostomy ≠ Laryngectomy

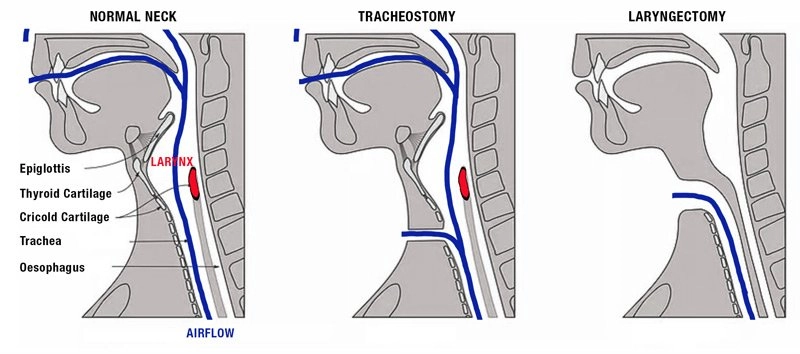

Do you remember those old school anti-smoking PSAs that included a woman with a trach putting a voice box to her throat to speak? This woman likely had a laryngectomy in addition to a tracheostomy. It is important to make the distinction between a tracheostomy and a tracheostomy combined with a laryngectomy as it will affect how we resuscitate the patient. A tracheostomy just involves making a hole in the trachea and sticking a tube in it. In many cases, trach patients can breath through their mouth and nose (eg. obstructive sleep apnea, ventilated). Some trach patients also have a procedure called a largenectomy, where their larynx is removed, their trachea is disconnected from their pharynx, and the only path for air is through their trach to their trachea.

Management of laryngectomy patients means no interventions involving the mouth or nose will help since the pharynx is only connected to the esophagus. Just keep it in the back of your mind that whenever this article mentions an intervention involving the mouth or nose (eg. endotracheal intubation), it does not apply to laryngectomy patients.

It is important to know that laryngectomy patients are the exception, not the norm: Over 100,000 are performed in the US in a year, while only about 3,000 laryngectomies are performed in the US annually (Tracheostomy Education 2025; Sykes 2023).

The Ins and Outs of Trachs

Tracheostomy tubes function similar to ET tubes. Some have cuffs like ET tubes, which can be inflated to hold the trach in place and prevent air leaking up into the pharynx instead of the lungs. Uncuffed trachs are used when patient isn’t on a ventilator and a perfect seal is not needed (eg. obstructive sleep apnea, tumor blocking airflow in upper airway). Uncuffed trachs are unfortunate in the case of a patient suddenly requiring ventilation in an emergency because the air leakage out the mouth and nose can make them ineffective (Nickson 2024). This problem can be solved by ventilating the mouth and nose while covering the trach, ventilating the trach while covering the mouth and nose, intubating through the oropharynx, or intubating through the stoma.

There is a device called an obturator, which is analogous to a bougie in ET tube terms. It is placed inside the trach tube when the trach tube is first being inserted into the stoma and is removed after the trach is in place. The obturator’s rounded tip sticks out of the trach tube and helps dilate the stoma before inserting the large-diameter trach tube. The use of an obturator is only relevant if we decide to replace a trach ourselves.

Unlike an ET tube, modern trachs are “dual-lumen”, meaning that they have an inner cannula inside the outer cannula. This may seem like a bad idea at first glance. After all, why would you want to add another cannula inside the outer cannula which would reduce the amount of airflow possible through the trach? Whatever reduction in airflow it causes, is absolutely worth it. When a patient’s trach is clogged with mucus and suctioning it all out is difficult, the entire inner cannula can be taken out to be cleaned and reinserted. It is important to note that routine suctioning does not require taking out the inner cannula but it should absolutely be part of your process if a patient is experiencing a blockage in their trach as it is your silver bullet to getting their airway patent again (LA County EMS Protocols 2010).

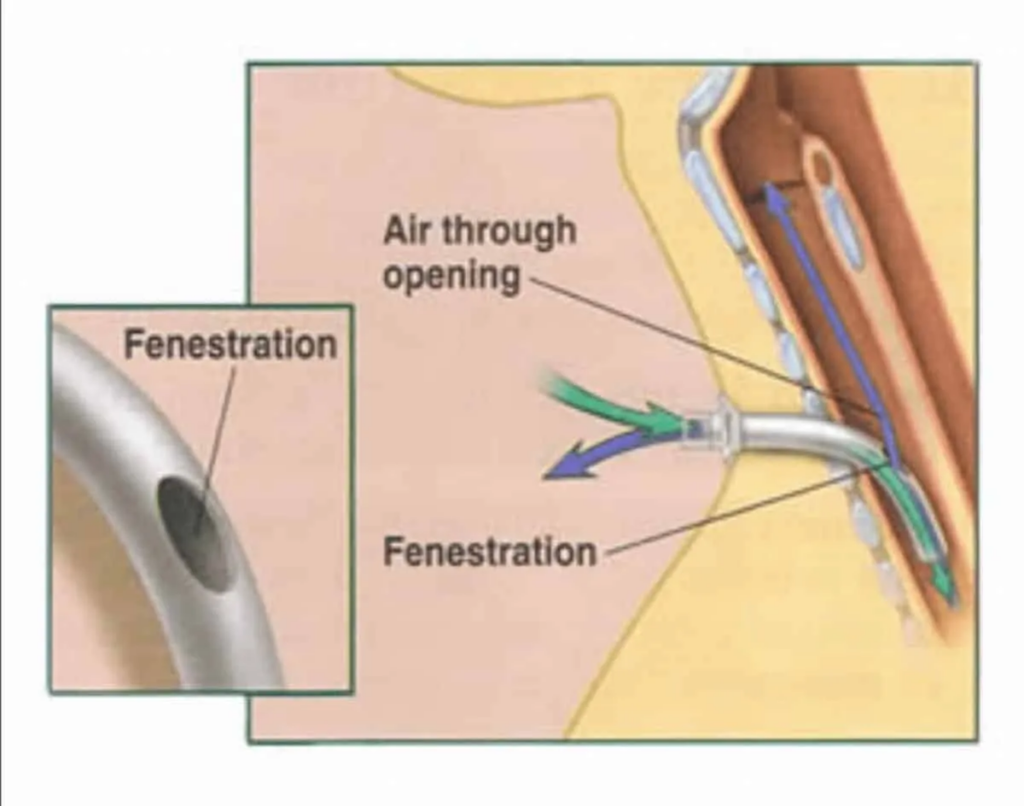

One minor nuance to keep in mind is that some tracheostomies are fenestrated, meaning they have a hole in them above the cuff (if a cuff is present). This is done so that the patient can get a little bit of airflow through their oropharynx, so that they can speak. Fenestrated trachs are relevant to us, because it means that we can still get ineffective ventilations, even with cuffed trachs. In this event, we have all the options we previously discussed (ventilate through trach and close mouth and nose, ventilate through mouth and nose and block trach, intubation through stoma, and intubation through mouth).

Emergency #1: Obstructions

An obstruction in the tracheostomy is one of the most common trach emergencies (Cooper 2021). Mucus and other secretions can build up in the trach tube and block airflow. Below is the procedure recommended for solving these obstructions: (LA County EMS Protocols 2010, Goel 2024)

- Preoxygenate patient through mouth/nose and trach if possible. Remember that most trach patients don’t have a laryngectomy and benefit from oxygen through the oral/nasal route.

- Deflate cuff if it is suspected that the cuff is occluding the airway

- Try to clear airway

- Remove inner cannula and clean with saline and suction (this solves majority of cases)

- If airway is still blocked, patient can be suctioned. Suction depth can be all the way at the level of the carina. This is necessary in rare cases because the patient is unable to cough so mucus builds up in the trachea, not just the tracheostomy. One tip is to dip the catheter in saline before inserting in the patient so that it doesn’t stick against the tracheal walls.

- An absolute last resort to clearing the trach is instilling 1-5 mL of sterile saline into patient’s trach tube in an attempt to dislodge any mucus. This should be a last ditch effort due to the high risk of pneumonia.

- Replace the tracheostomy tube. Trach patients or their facilities typically have spare trach kits that you can ask to transport with the patient.

- Endotracheal intubation or intubate stoma (advantages and disadvantages of both will be covered later)

Emergency #2: Hemorrhage (Uh Oh)

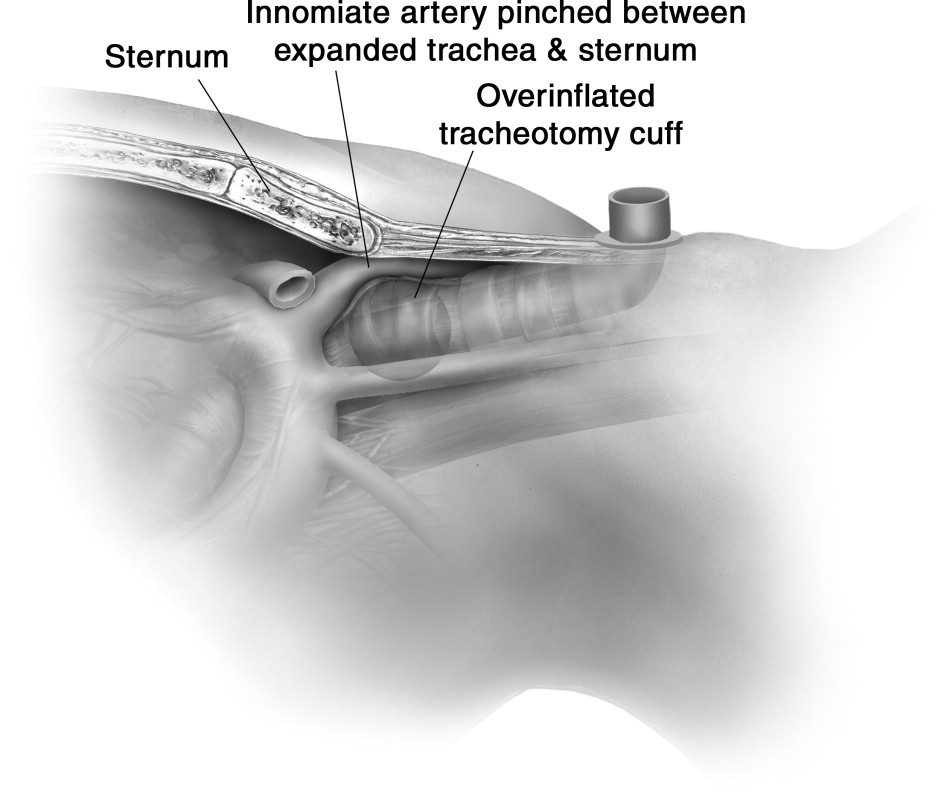

I included Uh Oh in the title of this trach emergency section for good reason. A bleed from a tracheostomy has the severity of a dialysis shunt bleed except even worse because it is inside the patient’s airway. Prolonged overinflation of a trach cuff can lead to the pressure from the trach balloon eroding the soft tissue around the innominate artery. This tissue necrosis results in the innominate artery merging into the trachea (called a tracheoinnominate fistula). It should be noted that some minor bleeding after initial insertion of trach tube, however, bleeding that is pulsating or occurring 3-4 weeks after tracheostomy should be suspected to be from an tracheoinnominate fistula. This bleeding has a nearly 85% mortality rate, however, there are still interventions we can do to try and improve patient outcomes: (Goel 2024)

- If tracheostomy is cuffed, you can try to overinflate the trach in attempt to tamponade the bleeding.

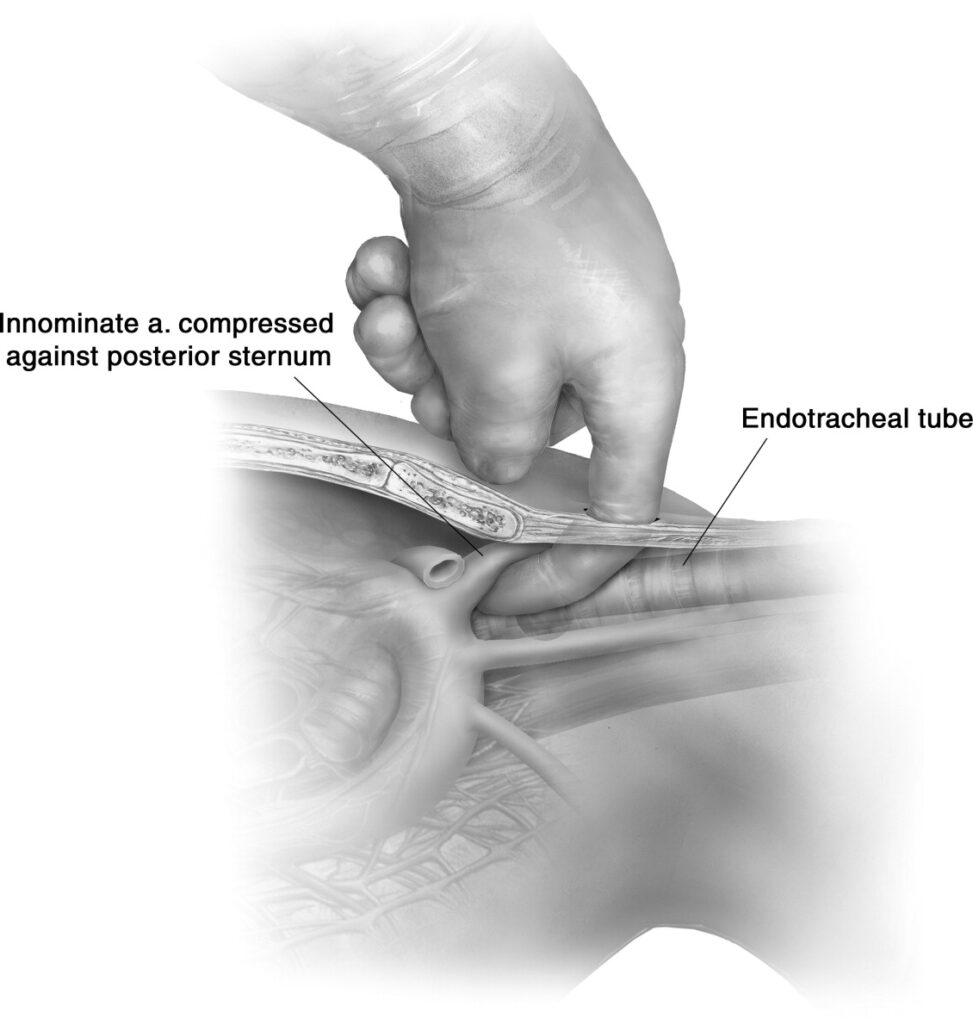

- If ineffective or trach is uncuffed, you can remove the trach, intube endotracheally, and insert finger into stoma pulling anteriorly to manually tamponade the artery (as shown in picture below). This procedure is surprisingly 90% effective at controlling the bleeding.

- Placing external pressure on the innominate artery by pushing on the posterior sternal notch with a finger to slow bleeding.

Emergency #3: Decannulation

Decannulation is the accidental removal of the tracheostomy tube from the neck. The most important information to know in this situation is when the trach was placed. If the trach was placed within the last 7-10 days, replacement of the trach or intubation through the stoma is contraindicated due to the fragility of the surrounding tissues. In these cases, endotracheal intubation is the go-to method. If the trach was mature (over 7-10 days old) when it was placed, then the trach can simply be replaced or endotracheal intubation can be performed. In some cases, no intubation or trach replacement is required by EMS because they are able to breath through their mouth and nose. (Goel 2024)

The Big Question: Intubate from Above or Below?

In cases where an airway needs to be established (eg. completely occluded trach that is unable to be suctioned adequately), there is the big question: should we intubate through the mouth or through the stoma? Factors supporting intubation through the mouth include a new stoma (new stomas are fragile and a false tract can be easily created when attempting stomal intubation) and signs of an easy endotracheal intubation. With an older, mature stoma and signs of a difficult endotracheal intubation, intubation through the stoma is indicated. Of course with laryngectomy patients, intubation through the stoma is the only option (Buckley 2025).

While covering intubation through the stoma, we should touch on use of the bougie. Some sources recommend intubating with a bougie (threading bougie through stoma or already placed trach, removing trach, and then sliding ET tube down bougie), while other sources advise against its use due to the fragility of the trachea and possibility for creating false tracts when inserting a hard bougie into the stoma (Buckley 2025; Gopal 2018). It is provider discretion whether they choose to use a bougie to intubate the stoma; however, if they use a bougie, they should be gentle with it to prevent damage to the airway.

Don’t Fear the Trach

Although there are some emergencies that a trach can cause (eg. tracheoinnominate fistula) and providers must know the basics of how a trach works to handle any respiratory call involving a trach patient, we shouldn’t fear managing trach patients. With an understanding of the anatomy of tracheostomies and a bit of problem solving, they are completely manageable.

References

Airway emergency – suctioning – tracheostomy tube & stoma. LA County EMS Protocols. (2010). https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/dhs/207403_Suct_Trach_Tube_SKILL.pdf

Andaloro, C. (2023, May 28). Total laryngectomy. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556041

Buckles, S. (2022b, August 4). Regenerating the larynx: A second chance at Speech – Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center blog. Mayo Clinic. https://cancerblog.mayoclinic.org/2022/07/26/regenerating-the-larynx-a-second-chance-at-speech/

Buckley, Jack. “Keeping Patients Safe during Emergency Tracheostomy Management.” Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation, 10 Oct. 2025, www.apsf.org/article/keeping-patients-safe-during-emergency-tracheostomy-management/. Accessed 11 Oct. 2025.

Cooper, Johnathan. “Tracheostomy Emergencies in Adults – RCEMLearning.” RCEMLearning, 30 June 2023, www.rcemlearning.co.uk/reference/tracheostomy-emergencies-in-adults/#1636711235059-67994bf2-f560.

Goel, A. (2024, March 25). Diagnostics and therapeutics: Tricks of the trach. Taming the SRU: Tricks of the Trach. https://www.tamingthesru.com/blog/diagnostics/trachtricks

Gopal, P. (2018, January 31). Troubleshooting the crashing patient with a tracheostomy. Aliem. https://www.aliem.com/troubleshooting-crashing-patient-tracheostomy/

Sykes, John J, et al. “Increasing Health Care Providers’ Knowledge of Tracheostomy and Laryngectomy.” Head & Neck, vol. 46, no. 3, 26 Dec. 2023, pp. 609–614, https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.27616.

Nickson, C. (2024, July 1). Respiratory distress in tracheostomy patient. Life in the Fast Lane • LITFL. https://litfl.com/respiratory-distress-in-tracheostomy-patient/

Tracheostomy prevalence. Pedistat. (2025, March 4). https://www.pedistat.com/blog/tracheostomy-prevalence

“What Is Tracheostomy? Basics of Breathing, Indications, Procedures and Benefits | Tracheostomy Education.” Tracheostomyeducation.com, Tracheostomy Education, 21 Mar. 2019, tracheostomyeducation.com/tracheostomy-basic-information/.

Leave a Reply